Could Covid-19 be the catalyst for change in Mozambique?

In recent months, social media users in Mozambique are likely to have come across an animated movie about Covid-19. The movie doesn’t talk about the downsides of the pandemic. Instead, it showcases the secondary impact the virus has had on the education of millions of children. Educational activists from the Mozambique national education coalition (MEPT) and partners hope that the video will encourage the country’s leaders to prioritize education amidst a global pandemic.

“COVID-19 came to show us that it is possible to have adequate school infrastructure. It is possible to reduce class overcrowding by building more schools and hiring more qualified teachers. It is possible to have a school that gives all children a possibility of a better future.”

This call for change comes at a time when the status quo is no longer an option. Many classrooms in Mozambique are overcrowded, lack qualified teachers and are void of basic sanitation and hygiene facilities. . While COVID-19 has provided many roadblocks to countries, it may also be the catalytic moment needed to create lasting change for education in Mozambique.

"Solve this and kids can go back to school without severe risk of spreading COVID-19. And solve this, and we would also see a much-needed rise in the general quality of the education in Mozambique,” says Pedro Mario Mazivila, program officer in MEPT. For years, the coalition has been working to increase the quality of education and advocating some of the exact same things that are now listed as prerequisites for the fight against the virus, namely more classrooms and more qualified teachers.

Quality and inclusive education on the agenda

Mozambique has shown its commitment to education. It has abolished school fees, provided direct support to schools and free textbooks at the primary level, as well as made investments in classroom construction. The sector receives the highest share of the state budget, over 15 percent.

MEPT was established in 1999 with the aim of enabling Civil Society Organizations to be involved in education and advocacy issues in favor of Quality Basic Education for All

MEPT is a network and a coalition of Non-Governmental Organizations, Associations, Community-based Organizations and Individuals who works to improve the quality of education in Mozambique

MEPT has 150 members including both organizations and individuals with an interest in quality education in Mozambique

The coalition carries out its activities throughout the national territory, having in each Province a focal point or representative, responsible for ensuring the implementation of the strategies, plans, policies and achievements of the results defined by the network

MEPT's website

“As a result, there has been a significant rise in primary school enrolment over the past decade. Yet quality and improvement in learning, has lagged,” says Pedro Mario Mazivila who hopes to be able to transform the Covid-19 crisis into a new point of departure in the quest for quality education for all.

Movimento de Educacao Para Todos (MEPT) was founded in 2000 with an initial focus on inclusion. While the enrolment rate grew, it was also obvious that some groups were left behind – girls in general, disabled children and children from the most remote and impoverished areas. MEPT and partners documented these inequalities and called for initiatives to bridge the gaps. These actions contributed to the government’s focus on girls’ enrolment and guarantee that– at least on paper – disabled children would have the right to education.

“Especially successful were our protests against a new ministerial order separating pregnant girls from their peers and transferring them to home schooling or evening classes, arguing that they would otherwise be of a bad influence. We managed to mobilize the public against this and lobbied hard for this decree to be withdrawn. Eventually it was,” says Pedro Mario Mazivila.

While the enrolment rate in Mozambique is around 75 percent, around one third of students drop out before third grade and less than half complete basic education. Moreover, the 2013 national learning assessment found that only 6.3 percent of grade 3 students had basic reading competencies. Assessments have also shown overcrowded classrooms, low quality of teachers (in 2014 a World Bank survey showed that only 1 percent of primary school teachers had the minimum expected knowledge) and high absenteeism among both students and teachers. On any given day around half of all children will be absent, and according to a 2013 World Bank sample, the same goes for 45 percent of teachers.

Creating change through dialogue

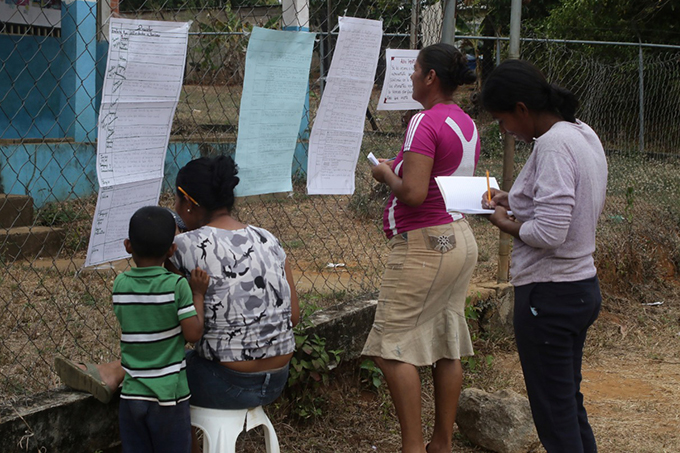

For MEPT, the road to change is through dialogue – it is crucial in their ability to influence as a valued and constructive partner for the government and the FRELIMO party, which has been in power since the country’s liberation in 1975. While MEPT is dependent on the government, the government relies on the contentedness of its constituents and this is the key to MEPT’s way of working. They research and monitor the situation on the ground, they mobilize parents and teachers to call for certain changes and they convey all this to the authorities while suggesting useful ways forward.

In this way, MEPT has also advocated the government to increase dialogue with civil society at the local level through local education groups. They have prevented the firing of thousands of teachers to decrease public spending – instead, the government decided to increase the national number of teachers. They have persuaded the government to train more teachers and start improving their working conditions. And they have gained support for a new initiative combatting widespread violence in schools with campaigns and a formal complaint mechanism and resources to follow up on reported cases.

“Going forward, our focus will be increasing the budget for education e.g. by increased taxation of the many multinational companies. We have suggested that the government review all agreements with these companies and erase widespread tax exemptions. We also work with the government to improve teacher training and set up transparent criteria for the hiring of teachers as a way to raise the quality and motivation of the teachers,” says Pedro Mario Mazivila.

Mozambique

Mozambique is ranked 181 out of 189 on the global humanitarian index with almost half of the population living in poverty (46,5 % in 2014).

After almost a decade of rather high growth, in 2016 the track record was disrupted when large, previously unreported external borrowing came to light. The revelation of undisclosed debt dented confidence in the country, increased debt levels, and more than halved the average rate of growth. In 2019, Cyclones Idai and Kenneth caused massive damage to infrastructure and livelihoods, further lowering growth and wellbeing of the population. The Covid-19 pandemic presents a further setback on the country’s economic prospects.

In recent years, Mozambique has made good progress in the education sector. The National Education System Law was revised in December 2018 and established a new structure for the sector, increasing mandatory (and free) education from seven to nine years. These changes and more investment and government commitment to keep education expenditure high have led to the progress.

Yet, efficiency challenges still plague the system. There are still almost two million primary-school-age children not attending school. More than one third of students drop out before Grade 3 and less than half complete primary, well below the average in Sub-Saharan African countries.

In upper primary, the gender gap increases, as more girls abandon school prematurely. Due to several factors including high levels of teacher absenteeism, children only have 74 out of the 190 expected school days in the year.

Sources

World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mozambique/overview Global Partnership for Education: https://www.globalpartnership.org/where-we-work/mozambique UNDP: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/MOZ