Façonner un avenir inclusif grâce

à l’Éducation à Voix Haute

Éducation à Voix Haute est le fonds du GPE dédié au plaidoyer et à la redevabilité sociale. Nous aidons la société civile à devenir active et influente dans l’élaboration des politiques éducatives afin de mieux répondre aux besoins des communautés.

Éducation à Voix Haute est le plus grand fonds au monde soutenant à la fois le plaidoyer de la société civile et la responsabilisation en matière d’éducation.

Éducation à voix haute est le fonds de plaidoyer du Partenariat mondial pour l’éducation (GPE), géré par Oxfam Danemark.

Nous transformons les systèmes éducatifs en renforçant les organisations de la société civile afin de mobiliser les citoyens et d’influencer les changements politiques dans le secteur de l’éducation.

Nos missions

Nous jouons un rôle de premier plan dans le renforcement de la transparence, de la responsabilité et de la participation civique dans le domaine de l’éducation.

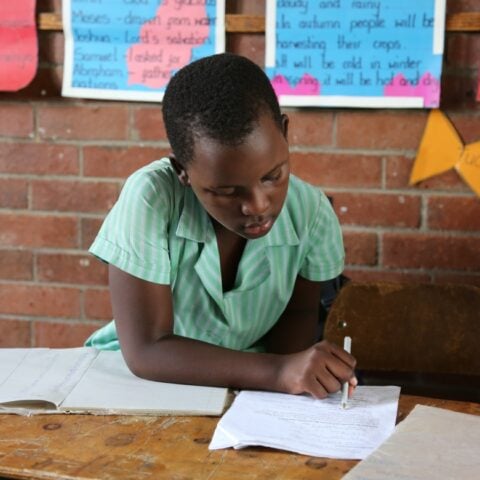

Nous amplifions la voix des groupes marginalisés afin de réduire les inégalités dans l’éducation.

Nous aidons les organisations de la société civile à élaborer des politiques éducatives adaptées aux besoins de leurs communautés.

Nous favorisons les partenariats afin de construire des mouvements éducatifs plus forts et plus efficaces.

Nous partageons nos connaissances et nos recherches afin d’inspirer l’action et le progrès de la société civile à l’échelle mondiale.

Notre impact

Changements dans la politique nationale

Au total, 188 réformes politiques

ont été adoptées pour rendre l’éducation plus inclusive et plus équitable dans 34 pays.

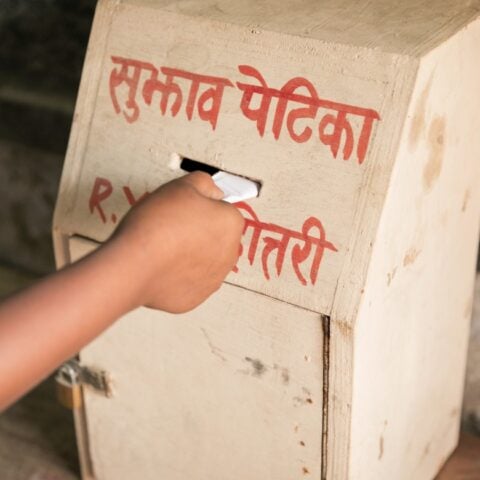

Redevabilité

sociale accrue

62 mécanismes de redevabilité sociale ont été créés ou renforcés

par les bénéficiaires d’Éducation à voix haute.

Connaissances et apprentissage

152 études, rapports ou évaluations ont été réalisés par les bénéficiaires en vue d’être utilisés à des fins de plaidoyer et de suivi.

Où nous travaillons

En 2024 , Education à Voix Haute compte 79 subventions actives dans 63 pays,

soutenant le travail de promotion de l’éducation.